Steve Coll’s new book on the origins of the Iraq War features transcripts of Saddam’s secret meetings. RCFP attorneys helped the author obtain them.

It’s been more than two decades since the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, starting a war that ultimately lasted eight years, cost tens of thousands of lives, and destabilized the Middle East.

Countless books and news articles have been written about what led to the Iraq War. Told largely from the perspective of western officials, most of them have focused on the United States’ post-9/11 hunt for weapons of mass destruction that we now know didn’t exist.

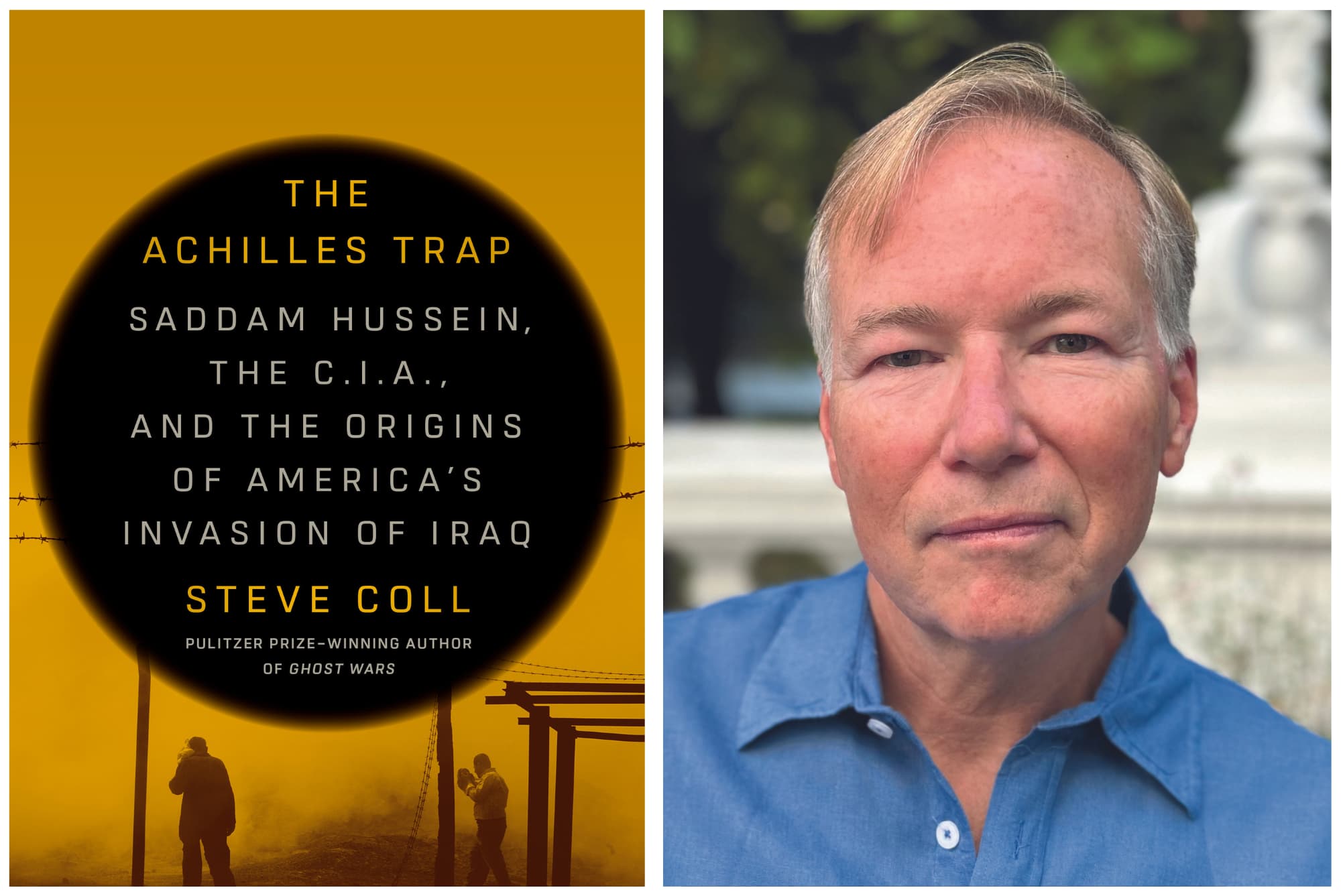

But a new book by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Steve Coll provides a fresh perspective on the origins of the war, one that explores the 2003 invasion through the two decades that preceded it and through the eyes of the brutal dictator at the center of it all: Saddam Hussein.

In “The Achilles Trap: Saddam Hussein, the C.I.A., and the origins of America’s invasion of Iraq,” Coll draws on a wide range of sources to tell a compelling, character-driven story about how the United States bungled its way into an avoidable war in Iraq. But some of the most revealing information in the more than 500-page book comes from transcripts of tape-recorded meetings from inside Saddam’s regime, including many materials never before published, which were captured by invading U.S. forces.

As Coll notes in the book’s introduction, he obtained a cache of 145 transcripts and files after settling a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit against the Pentagon with free legal support from attorneys at the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. He also received additional records from the private archive of scholar Michael Brill.

“By connecting these and additional parts of the captured files with other sources, including interviews with surviving participants,” Coll writes, “it became possible to see in new ways what drove Saddam in his struggle with Washington, and to understand how and why American thinking about him was often wrong, distorted, or incomplete.”

Ahead of his book tour, the Reporters Committee spoke with Coll about why he decided to team up with RCFP attorneys for the project, how the Saddam tapes provided the book’s narrative voice, and what the U.S. government can learn from his research about how to deal with other authoritarian foreign leaders. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Given that there has been so much written about the origins of the invasion of Iraq, why did you decide to write this book?

Primarily, I felt that the mystery of why Saddam did as he did was a neglected part of our understanding of the origins of the decision to invade. Our self-reflection and political arguments about the invasion had concentrated — understandably — almost exclusively on the decisionmaking in Washington and in London about the threat Saddam seemed to pose, about the bad WMD intelligence, about the public selling of the war, about the media’s involvement. All of that had been the way that we had come to terms with the invasion and the discovery that the premise that Iraq had WMD was false.

But why had Saddam created the impression that he had WMD when he didn’t? Why did he risk his long run in power and ultimately give up his life for weapons that he didn’t possess? That was a question that was almost never asked. And when I learned about the tapes and the other records from his regime, I thought that perhaps there would be a way to tell a multi-sided story to include his part of the bargain into our understanding of where this came from.

The tapes you just mentioned were part of an archive that was briefly made available to the public before being withdrawn in 2015. What did you expect to learn from them once you found out that they existed?

I wasn’t sure. There were a fair number of materials in a scattershot way that I could access to get a flavor for what they read like, what they felt like. There were conferences that had released excerpts of some transcripts and those materials were still publicly available. I thought they were interesting because they provided an authentic and very unusual case study of the thinking and decisionmaking of a dictator in a closed system, one whose actions and thinking ended up having an enormous impact through the Iraq War on the United States. It’s just unusual to get that level of real-time transcripts, even in the U.S. political system.

My ambition was to add to the record substantially by filing a FOIA request that could draw out new materials that maybe had never been released or that were no longer available and still seemed to be important.

Why did you decide to team up with Reporters Committee attorneys when requesting these records from the Pentagon?

In a couple of previous books, I had filed FOIA requests on my own and had had slow but good experiences with extracting useful materials. In those cases, I had a sense of what I was looking for. I would send in my FOIA requests like a stranded survivor throwing a message in a bottle into the sea, hoping that something would come back. Sometimes, in the case of the Exxon book, I didn’t hear anything for a long time and I thought, “Oh, this is just pointless. I’m never going to get anything.” And then suddenly, these large envelopes started arriving at my home address some years after I had filed the requests, and I would rip them open and discover what turned out to be good and important materials.

This time, I thought, “I can’t afford to do it that way. I need professional assistance. I have to run on a more predictable timeline. These materials are too central to the project for me to go alone.” So I called the Reporters Committee, and [RCFP Senior Staff Attorney] Adam [Marshall] ended up being my point of contact. He was incredibly helpful in just laying out a process for how I should proceed individually as a filer and what timeline to expect by way of the government failing to do its duty in responding, and then once enough time had passed, then we could talk about litigation. The whole plan made good sense to me, and so that’s what we did. And it unfolded almost exactly the way Adam predicted.

How did you go about crafting your FOIA requests to increase the chances that you would get the records you needed?

My hypothesis about what I should file for was partly based on my own experience with federal FOIA, which is not a great system, the advice I got from Adam and the team, and my analyses of some indexes that were publicly available that provided lists of transcripts, tapes, and other documents with short descriptions saying what they described, and they had dates, so I could see when a conversation had taken place. So I looked through as many indexes as I could find, and I thought — and Adam agreed — that I should ask for files that were listed in these indexes because they had identification numbers that would make it very easy to locate them so that the government couldn’t say, “I can’t find them, or I have to go dig around a warehouse in Qatar” or something like that.

I limited my request to items that were indexed, and then I decided to ask heavily for more recent files because, looking at what was available through scholarship and detritus on the internet, there was a real absence of material from after 9/11 and right up until 9/11. There was a strong bias toward material from the 1980s and 1990s, and I think it was because of the controversies around WMD after the invasion drove a lot of the selection process in the first releases of these materials. People wanted to know, “What was the history of the chemical weapons program? How did Saddam talk about using WMD?”

There was less on the record about what Saddam was saying and thinking after 9/11. And I was very curious as to why that was and wondered if there was a political bias. Maybe the tapes were embarrassing in some way. I can’t explain why there was so little of that material on the record, but once I saw some of those meetings, they were very interesting, and I think they worked really well to bring a completely fresh perspective and voicing onto the page in the part of the history that I figured would be the most familiar to readers, from 9/11 to the invasion. It was challenging because it was the more picked over part of the history, and I had these materials to kind of rewrite the history with Saddam’s voice very much present.

With support from Reporters Committee attorneys, you eventually sued the Pentagon. After reaching a settlement, the government turned over a cache of 145 transcripts and files, including many never before published. What was your reaction when you finally had a chance to read through them?

Well, there’s some good stuff (laughs). That’s the main headline.

It’s Saddam’s view of the world at critical junctures [leading up to the invasion of Iraq]. It’s the totality of his mindset: his concerns, his paranoia, his conspiracy theories, his reading of the Americans. I would say that is probably over and over again the most interesting thing for the audience that I was trying to write for, which I think isn’t just an American audience, but an international one as well. How did Saddam see his own adversaries? We had a theory of him, what was his theory of us? He was very shrewd about matters of power. Obviously he had taken power in very rough circumstances and held it under pressure for a long period of time, so it wasn’t surprising to see that he was obsessed with his adversaries and with matters of power and competition among militaries and governments, but the way he thought about that, the way he read the Americans, the way he made his own decisions about whether to cooperate, whether to be aggressive, was absolutely fascinating.

The bonus points were that he was lively. He could be a drudge — he rambled on about geopolitical matters and no one ever interrupted him because why would you interrupt someone like that? — but he did have a sense of humor. He could be charismatic. There was just an energy in his presence that made it easier to write about him.

You write that the U.S. government repeatedly misjudged Saddam and made a series of avoidable errors in assessing his intentions. What can the U.S. government learn from your book as it seeks to understand other unpredictable, authoritarian leaders, like Vladimir Putin in Russia and Kim Jong Un in North Korea?

As a writer, I had the space to try to really empathize with Saddam, and I had the information available to try to do that in some depth and to try to see the world from behind his eyes. I think you can’t help but come away with a sense that, in contemporary affairs, even though we may have a surface impression of adversarial authoritarians, the Saddam case cautions that, in such closed systems, there are almost always many layers of truth behind the surface presentation of a leader that will explain much more than what’s visible.

One lesson is that it is in our national interest to maintain contact even with our enemies, even when it’s morally uncomfortable, even when it’s politically fraught, because these systems are so closed and there are limits to the insights that are available through other means. It doesn’t have to be the president picking up the phone and calling his counterpart. But in Saddam’s case, we didn’t have contact with Saddam or any of his envoys through any channel for like 12 years before the 2003 invasion. In hindsight, that was clearly a mistake. Would we have learned if we had been talking to him or his people that he had kind of lost interest in military affairs toward the end and was obsessed with novel writing? Would we have learned that he issued orders to scientists to make sure that all of the weapons were destroyed and that the documentation was eliminated? Would that have caused us to pause and think, “Why is he issuing orders like that?” Who knows, but we certainly didn’t encounter those facts because we had no access at all.

Why do you think the U.S. government didn’t try to communicate directly with Saddam or his closest aides over all those years? Were the politics just too sensitive?

Yeah, that’s the answer. There was a conversation between [President Bill] Clinton and [British Prime Minister] Tony Blair in 1998, when they’re talking about Saddam, and Clinton asked Blair, “Has anyone in your foreign ministry talked to Saddam over the last few years?” And Blair’s like, “I’d have to check. I don’t think so.” And Clinton says, “If I could, I’d pick up the phone and call the son of a bitch, but it’s so fraught in America that I would just be roasted if I did that, so I can’t. But I sort of feel like we should be talking to him.”

And it’s clear from the records that Saddam would have been happy to have a backchannel through his intelligence services or through his family members or any number of channels if we had appointed someone on our side to have those conversations. Would they have been very fruitful? Hard to say. But what is the cost of doing that? Not very high. It’s only in domestic politics. And Clinton’s comment to Blair shows you how intense the pressure is in the White House not to be seen as compromising. And it’s not only about a president’s political or popular standing, it’s also that, in these cases, as today, we have sanctions regimes in place. And the effect of the sanctions regimes depends on compliance by allies. So there are good reasons why it doesn’t happen, but you’re asking an important question, which is, what can we learn from our past failures? And one of them is that you really can’t afford to be silent if you think that this adversary can hurt you.

“The Achilles Trap” skillfully weaves information from the transcripts and many other records together with the narratives of a huge cast of characters, including CIA agents, scientists from Iraq’s nuclear weapons programs, Saddam’s victims, and many others. Why did you decide to tell the story in this way?

It’s kind of the only way I know how to do things, to be honest (laughs). It’s what I read, it’s what I have done before. My niche is to try to synthesize intelligence, political, and military history around America’s encounters with the world, particularly our failures, when we go out and struggle in complex and emerging countries like Iraq or Afghanistan or Pakistan. I’m drawn to the challenge of trying to get the big picture into the book while making it readable. And to me, making it readable means you need characters and you need scenes and dialogue and action. And you need to keep it as brisk as you can while not compromising on the complexity of what’s going on.

I’ve been practicing this for a long time. And I felt like what was so satisfying about this project was that I could deliver a much higher ratio of fun characters and dialogue and action than I normally can because the transcripts were so lively, because Saddam was kind of a larger-than-life character, and because there was so much action behind the scenes: the defection of [Saddam’s] son in law, coup attempts by the Americans one after another, a couple of wars.

Working in this genre for so many years, I don’t often have material that is like that, start to finish, and I was really grateful for it. It was fun. That was the gift of the transcripts. They provided a bedrock of narrative and voice and dialogue that is essential to make a complicated history like this readable.

What was it like working with Reporters Committee attorneys on this project?

The Reporters Committee was just invaluable to this whole project. It was a huge gift to have that collaboration. They are great lawyers. They are really committed to the goal of public interest work. They were very collaborative and careful to make sure that what we were doing was something that I understood and they gave me good, honest advice. I come from a family of lawyers, I live around lawyers, and so I appreciate them. But I also recognize best practices. And they were just excellent. I also thought they were hugely effective and efficient. We didn’t waste a lot of time going down rabbit holes. They know their business so they were able to accurately predict and manage the process so that we got a great result without a lot of distraction.

The Reporters Committee regularly files friend-of-the-court briefs and its attorneys represent journalists and news organizations pro bono in court cases that involve First Amendment freedoms, the newsgathering rights of journalists and access to public information. Stay up-to-date on our work by signing up for our monthly newsletter and following us on Twitter or Instagram.