Reporters Committee analysis of U.S. government indictment of Julian Assange

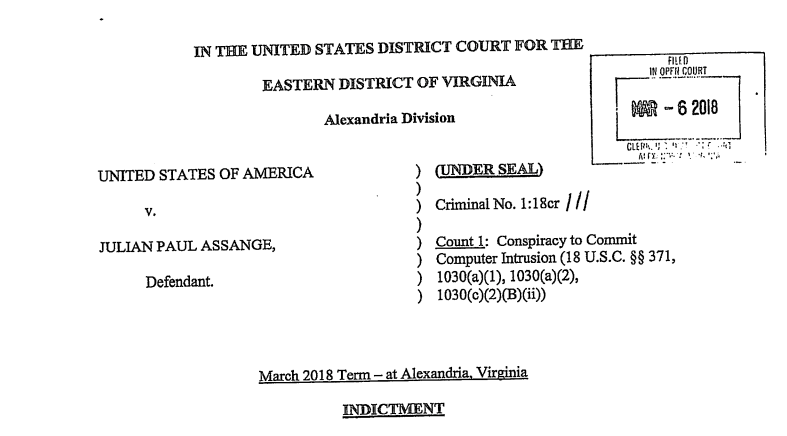

On April 11, British police arrested WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange at the Ecuadorian embassy in London, in part because of an extradition request by the United States. Following the arrest, the Justice Department released a previously sealed indictment charging Assange with one count of conspiracy to violate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, a 1984 law meant to criminalize hacking.

It’s a spare indictment, and other charges could be brought. But in terms of how this specific development could impact press freedom, as with all things, the devil is in the fine details.

The discussion below explains the allegation, as we understand it, and why it makes this particular indictment a hard model for future prosecutions targeting the press. The latter two sections lay out how a case with different facts but a similar “look” could directly violate the First Amendment.

What the Justice Department Says Happened

The indictment includes an allegation that the Justice Department must hope is a viable CFAA violation, at least for the purposes of this indictment and securing Assange’s extradition. Prosecutors claim that Assange agreed to help Chelsea Manning “crack” a password to a Defense Department computer. Here’s what that means:

In cryptography — code making and breaking — one can take a password of any length and represent it as a fixed set of numbers and letters. That alphanumeric string is called a “hash value” and it’s created by a “hash function” (a method of calculating that value).

Hash values are a shorter and secure code for another piece of data, like a password, that have two key features. One, it’s difficult to reassemble the original password from the hash value. Two, small changes in the password result in starkly different hash values. To oversimplify, the hash of the Spaceballs password “12345” might look like “AE2D” but “21345” could be “B9G6.”

To reassemble a password from a hash value, one needs to use a computer to rapidly calculate possible hashes until you get a match. The computer would hash “12345,” “12346,” “12347,” and so on, until the hash value matches. Computer security researchers and technology reporters do practice password-cracking, in part to gauge the security of passwords given the ever-increasing sophistication of password-cracking techniques.

But, the Justice Department indictment alleges three key facts, that, if true, form the kernel of the CFAA case. One, Assange agreed to assist Manning in cracking a password. Two, Manning sent Assange a hash value for someone else’s password. And three, Assange said that he tried to crack the password and that he asked for more information about the password. It’s important that the password was for SIPRNet, the Secret Internet Protocol Network, which carries Defense Department information classified at a “secret” level.

The Justice Department also alleges as part of the CFAA conspiracy that Manning booted the SIPRNet computer with a Linux operating system that allowed her to access the hash value. For complicated reasons, that’s a more difficult “hook” for a CFAA claim because it’s less clearly in line with what Congress intended the CFAA to cover than unauthorized access to a government network through a cracked password.

In sum, the plan, as alleged in the indictment, was for Assange to crack the password, send it back to Manning, and Manning would use the password to access SIPRNet and collect classified material.

The CFAA has been held to cover a lot of innocuous activity online — for instance and as discussed below, using automated means to collect public information online and engaging in certain activities that violate websites’ terms of service — but password-cracking is the kind of activity that Congress had in mind when it passed the CFAA. The law has been dramatically and troublingly expanded since its passage in the mid-1980s, but the legislative history expressly cites concerns over how the “personal computer” permits users to rapidly guess at access codes or passwords.

As noted, another driving concern of the law was unauthorized access to government systems. Its genesis was an early screening of the movie “WarGames” for President Reagan, in which teenage hacker Matthew Broderick accesses a NORAD supercomputer. Interestingly, the Broderick character did not guess a password. Instead he happened upon an open phone line to the computer using a technique called “war-dialing” (having a modem call numbers until it connects with another modem). But the government intrusion angle led to the first presidential cybersecurity directive and ultimately the CFAA.

Importantly, it wouldn’t be enough for Manning and Assange to just share passwords, which people do all the time, and it’s not a crime for an outside person to receive a password even to a government system. What’s crucial is that Assange himself allegedly promised to attempt to reassemble the password from the hash value as part of a claimed conspiracy to log into SIPRNet using a different person’s credentials and to exfiltrate classified information.

That allegation — conspiring to crack a password to a Pentagon computer — isn’t something that a newsroom lawyer would counsel a reporter to do. It’s also a different case than if a journalist received an encrypted video or file and tried to figure out how to get into it (just like if somebody delivered a government lockbox with classified documents to a newsroom and reporters tried to open it). The CFAA is vague, overbroad, and parts of it are consequently likely unconstitutional, but using a computer to crack a password to a classified government network was one of the main concerns that drove passage of the law.

Using the CFAA in Leak Cases is Concerning

Even if the risk of a similar claim against a newspaper would be low, some civil liberties groups are raising the alarm. Why are they doing that? In part because a CFAA claim on slightly different facts, namely without the SIPRNet password cracking, would be troubling — particularly for data journalists, computer security practitioners and internet researchers. It would be especially bad in a leak case. Here’s how that might work, at least in theory.

Assange is charged with one count of conspiracy to violate three provisions of the CFAA. The most important is the first section of the law, 18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(1). That section incorporates language from the Espionage Act, the 1917 law that the Justice Department has increasingly used to prosecute reporters’ sources in the government as if they were spies.

Section (a)(1) makes it a federal crime to hack into any computer (not just government computers) to obtain national security information “with reason to believe that such information so obtained could be used to the injury of the United States, or the advantage of any foreign nation” and then to “willfully” communicate, deliver or transmit that information to someone not entitled to receive it. The provision also covers attempts to do the same thing or willfully retaining the information and not returning it to the government.

This is the kicker — there’s no definition in the law of “hacking.” Rather, the CFAA refers only to accessing a covered computer “without authorization” or in a way that exceeds authorized access. Both the government and private companies, who can bring a civil CFAA claim or refer criminal charges to the authorities, have successfully argued that “without authorization” encompasses activity that many computer security experts do not consider “hacking,” and indeed that data journalists engage in on a daily basis.

Most prominently, data journalists will often “scrape” the web through computer programs that automatically collect publicly available information online. Many websites prohibit scraping in their terms of service, and terms of service violations have been found to constitute access to a computer “without authorization.”

Data journalists also often use accounts under a different or fictional name, particularly when trying to identify racial, gender or other forms of discrimination online. Those likewise will violate a website’s terms of service, and therefore possibly the CFAA.

Government efforts to deploy the CFAA in this fashion in a leak case would be an extreme overreach, but because of this weird mash-up of the Espionage Act and the CFAA, the worst-case scenario would be something like an Internet-age update of the Pentagon Papers.

The Pentagon Papers were a multi-volume, top-secret Defense Department study of the Vietnam War, and contradicted many of the official explanations for the origins of the conflict. Two of those copies were sent to the RAND Corporation, which had helped prepare the study. Daniel Ellsberg, a RAND employee who had worked on it, and his friend Anthony Russo physically copied and leaked the document.

Let’s say the Pentagon Papers went to RAND today. The RAND website expressly prohibits any reproduction, duplication or copying of any part of its site for any commercial purpose without permission. Let’s further say that instead of physically photocopying the Pentagon Papers and delivering them to The Washington Post or The New York Times, Ellsberg posts them to a publicly accessible portion of the RAND website and sends a confidential tip to a reporter. The reporter goes to the site, copies the files in violation of the terms of service, and publishes them on the reporter’s website.

To be clear, a federal criminal complaint in this case is more of a law school exercise than a real-world concern (though the hypothetical itself is quite plausible). Additionally, The New York Times and The Washington Post would have strong First Amendment arguments, not least of which are well-established constitutional protections for the publication of lawfully acquired information, even if it was acquired illegally by a source.

But the possibility of a truly damaging leak, even if squarely in the public interest — and the most damaging leaks usually are — can make governments do crazy things. And even some well-meaning government lawyers will adopt aggressive legal theories when “playing to the edge,” as former CIA Director Michael Hayden put it in the title of one of his books, particularly in the face of an actual or perceived national security threat. The potential for misuse of the CFAA under different facts, but a similar theory, cannot be entirely discounted.

The Complaint Alleges a Broader Conspiracy Than It Needs To

While the “hook” the government uses is the password cracking, the allegations in the indictment could, but do not, end there. The complaint could have simply alleged the key facts noted above: Assange agreed to crack the password to a classified network, received the hash value, and attempted to crack the password. It doesn’t matter whether he succeeded.

Instead, the complaint uses language tied to the receipt and publication of classified information more broadly. For instance, it alleges that the “primary purpose of the conspiracy was to facilitate Manning’s acquisition and transmission of classified information related to the national defense of the United States so that WikiLeaks could publicly disseminate the information on its website.” (See paragraph 16 of the indictment.)

And, in describing the “manner and means” of the conspiracy, the indictment alleges that:

- Assange and Manning used the online chat program “Jabber” to “collaborate on the acquisition and dissemination of the classified records” (paragraph 18);

- That they “took measures to conceal Manning’s identity as the source of the documents” (paragraph 19);

- That Assange “encouraged Manning to provide information and records from departments and agencies of the United States” (paragraph 20); and

- That Manning and Assange “used a special folder on a cloud drop box of WikiLeaks to transmit classified records containing information related to the national defense of the United States” (paragraph 21).

The parallels between what a member of the news media does on a daily basis ought to be obvious. Reporters and sources regularly use encrypted communications applications to “conspire” and to pass information back and forth (as well they should). Reporters go to jail to “conceal” the identity of their sources. Reporters frequently flatter sources to elicit information. And most newsrooms today have secure means for the anonymous submission of government secrets that are much more sophisticated than a “cloud drop box” circa 2010.

It’s unclear why the government chose to include the language about concealing Manning’s identity, encouraging Manning to leak, setting up a system for transmitting the files or communicating with Manning over an instant messaging service. The basis of the charge is the specific allegation that Assange and Manning conspired to crack a SIPRNet password; the rest could be read as surplusage.

Indeed, those allegations look similar to language in the complaint against James Wolfe, the former security director for the Senate Intelligence Committee who pled guilty last year to making false statements to the FBI in a leak case (not an Espionage Act charge). Several allegations in the Wolfe complaint about his interactions with the press also seemed extraneous. The Reporters Committee dove deep on that case here, in part because it was the first Trump-era case we know of involving a records seizure from the press. We annotated the complaint in the case to highlight the language that went beyond the false-statement allegations.

Time will tell how this plays out. It bears repeating that no one is outside the protection of the First Amendment. The singular allegation that Assange may have attempted to crack a password takes this case out of the “easy” category for press freedom advocates. The government would be mad, reckless — or, worse, actively anti-democratic — to bring a similar case without the password-cracking angle. But the possibility, however remote, is there. And if it happens, that will be a legal battle to equal the Pentagon Papers case.

Please note that the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press is actively engaged in legal efforts to ensure transparency in this case so the public can understand the First Amendment implications of the charges against Assange. The Reporters Committee also joined an amicus brief in support of Wikileaks in a lawsuit brought by the Democratic National Committee based solely on charges that Wikileaks received and published emails hacked from the DNC.